I had the good fortune of studying creative writing with Carolyn Smart when I was an undergraduate student at Queen’s and it was she that introduced the name Bronwen Wallace, with whom she was friends, into my frame of reference. That, however, was over a decade ago. Reading goes slowly, you see, and so I never made it to any of Wallace’s work until now.

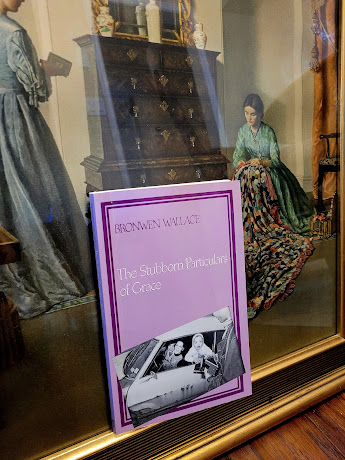

The Stubborn Particulars of Grace is a collection of poems that veers towards confession, eulogy, and activism. The whole collection reads as incantatory and dedicatory in nature, with poems for specific people. It recalled to me some of the advice in Anne Lamott’s book Bird By Bird, where she discussed how her best writing begins as a gift to someone. Wallace embodies that: these poems feel like gifts, sometimes to a fault—the gifts needs to be broad enough to be stolen by others. In any case, the collection is deeply personal, but also has an outward focus towards social causes and community-building. To that end, the conflicted tenderness in the treatment of inmates at Kingston Penitentiary really shone.

In terms of style, Wallace’s individual lines aren’t as flowery, ornate, or challenging as you might expect from modern poets. Her style is direct and straightforward, almost as if her poems are more like short stories than densely packed constellations. The style has its pros and cons; the poems don’t really grip me with their language, but the length of the poems offer some great opportunities for circling back to a core motif or playing with juxtaposition in interesting ways. The unlikely connections and associated meanderings were the most engaging pieces.

There are five poems in particular that stood out to me that I’d like to offer some commentary on here: “One of the Things I Did Back Then”, “Gifts”, “Joseph MacLeod Daffodils”, ”Testimonies”, and “Neighbours”.

In “One of the Things I Did Back Then,” the opening stanza is focused on deeply personal involuntary memories. In describing summer, Wallace writes that the smell of summer “isn’t roses or freshly mown grass” but is instead the “hot-baked dusty steam / that rises from the pavement / just after the street cleaner’s gone, gritty / and warm as any memory worth the work.” She then proceeds to jump between connected memories, smelling decaying newspapers in the library and reading through birth and death announcements. It’s a morbid scene where the speaker writes down a list of the names of children who died in infancy for someone else. The narrative builds a mysterious premise as the narrator speculates on where this man might be and then the second stanza takes a surprising turn: “When he deserts, / his real name becomes a skin / he has to shuck, so he can wear / the one I’ll give him, a dead child’s, / that allows him a birth certificate, / a social insurance number, a chance.” In a short vignette, Wallace builds a life, presumably for a draft dodger or a Vietnam veteran, because the next stage recounts watching movies of young men getting pushed from helicopters and children bursting into flames and “a war coming at me, not from the TV / but through my own front door, born from hands / that dried dishes or made soup.” To her credit, Wallace builds the milieu and fills it with real, flesh-out characters with a great deal of economy. The speaker of the poem confesses to feeling conflicted and the ethical dilemma of the piece comes across with such confessional beauty it’s hard not to be engrossed by it. She notes, “Mostly I see what I did back then / as a way I had to help them, / but sometimes I think about the parents / of the babies whose names I stole, how they’d feel / if they knew and whether it was a kind of violation.” She describes the excitement of finding a new identity “like winning a lottery, / and how the names, the two dates / made the cards I used look a little like tombstones.” I find the juxtaposition of light and dark in the poem plays beautifully—tragic, but beautifully. The end reflections demonstrate introspection as personal as universal in its implications:

Here, we know only too well

the chances a name offers

or denies. The difference it can make,

like the bit of luck or the casual decisions

that add up to a lifetime.

Here, I know, too, that the war

I thought I had a tiny part in stopping

merely shifted location and goes on

as planned.

She finds the universal core of the experience to share before ending the poem with a personal reflection on her own birth announcement and passing into history to do her part. I feel like the poem “One of the Things I Did Back Then” serves as an excellent reference point for Wallace’s ability to navigate the personal, political, and universal effectively.

Her poem “Gifts,” appropriately so named, given the nature of the book, begins again with a deeply personal moment: “Right now, my son is crying / because the T-shirt be bought me for my birthday / is a bit too small.” Even beginning the poem with those two words, “right now” gives the poem an immediacy and grounds it in “reality” (or as close to it as text can come). Her son’s sobs are described as “stubborn intervals / that try to force a song apart,” which is such a wonderfully poignant phrase. From there, the poem becomes somewhat list-like in the reasons that Wallace would still wear the shirt: “it’s not that small” and “because of the Mickey Mouse decal” and how it is personalized with her name, and he saved up, and she’s his mom, and so on. The sentiment her son feels I find relatable: you know the gift isn’t perfect and it’s devastating: “He can see for himself how it wrinkles / under the armpits and clings / to my shoulder-blades.” The feeling is compared to that of an argument where “words we let fly [...] [are] dry birds, in some empty room of the brain” — another great image to ground the experience. The poem then delves into memory of watching him grow and become a man and find his place in a masculine world and that disconnect that forms noticeably, suddenly.

As I mentioned before, the length of the poem allows Wallace to explore a motif and forge unlikely connections, which may be best represented by her poem “Joseph MacLeod Daffodils.” The poem starts with dialogue where someone tells the speaker that she’s planting perennials because she’s scared and says, “because I’m scared and it’s the only way I know / to tell myself I’m going to be here, / years from now, watching them come up.” There’s some meditation on what kind of milestones can be marked by the growth of plants—“when Jeremy / is old enough to drive, I’ll have to divide these, / put some under the cedars there; by the time / he leaves home, they’ll be thick as grass.” There’s then an extended discussion that offers a view to the intimacy between the characters, hovering around the idea of death and staring down the inevitability of it. As the two share ideas back and forth, the speaker shares knowledge that there are yellow daffodils called Joseph MacLeods, and that the way “they got their name / was that the man who developed them / always kept a radio on in the greenhouse / and the day the first one bloomed, in 1942, / was the day he got the news / of the Allied victory, against Rommel, / at el Alamein, and the announcer who read the news / was Joseph MacLeod.” She says it’s a “sense of history” that she can appreciate: “no El Alamein Glorias or / Allied Victory Blooms for this guy, you can be sure. / It’s like the story my mother always tells / about joining the crowds on V-E day, swollen with me, / but dancing all night, thinking now / she can be born any time.” The conversation shifts over to another long stanza that discusses Diane Arbus and cancer and divorce and the existential dread being spread out between them. There’s a direct address to the interlocutor in the final stanza: “It’s what I love in you, Isabel. / How you can stand here saying / ‘Brave and kind. I want to get through this / being brave and kind.’” By the time the last stanza arrives, several of the key motifs return and the way the flowers and Joseph MacLeod and their shared love of quotations serve as touchstones that enhance the themes of the poem with a final observation that the more a secret tells you, “the less you know,” offering this enigmatic note to end on, with questions about mortality and immortalization hovering just above.

The poem “Testimonies” is a compelling, fraught work that meditates on language. It praises an old woman’s voice that serves as a guide for “her people.” The poem is seemingly focused on an Indigenous experience from the outside as people strive to document languages: “the long hours / taping these languages which only a few / of the elders speak now.” It’s a poem about sharing stories, but also about having to “create the alphabet / that takes them there.” The poem then becomes an extended metaphor of map-making and language-making as co-extensive. There’s a beautiful anecdote about a parrot in the Northwest Territories that lived for sixty years after being brought over and how it sung songs in a cockney accent, “the voice of a dead miner / kept on in a brain the size of an acorn.” There’s a compelling moment where “all countries of his lifetime, contracted / to its bright, improbably presence / amid men who figure they’ve seen / just about everything now.” There’s a compelling contraction of space and language that nonetheless retains a connection to the outside, a thread to follow to something bigger. Again, the juxtaposition in the poem plays well. There’s this small link to the past through the parrot, and then it’s expressed again from another angle with shards of pottery popping up in layers of earth, then shifts to a meditation on how we slow down to look at car crashes and scan the wreckage, “blessed by our terrible need to know everything.” Further, there’s a man who ploughs a skull up in his cornfield that long goes unclaimed. Then, there’s a comment on the fields being enriched by deposits of a glacier. The whole poem is snapshots of the past that linger: “the trunk of old clothes / or the chair that didn’t make it / to the load on back of the truck” and “those smaller choices / we all have to make / about the future / and what can be wisely carried into it.” If there is one poem in the collection that is a masterpiece, it is this one. Everything is finely wrought and cohesive.

Finally, I’ll make a brief comment on “Neighbours,” which has lush imagery and comments on the idea of perspective. It notes that “insects see / as ultraviolet, a luminescent landscape / we can’t use, though the city / rises from it, scared and hopeful, / like a friend I haven’t seen in years.” The fact that this passage about perspective and invisibility emerges within a poem about inmates is a brilliant turn. Again, the juxtaposition really works. Insects see invisible worlds that we don’t, and prisoners are literally removed from our sight. It’s an exercise of imagination, of perception-based empathy, even for people who have done reprehensible things—a challenge Wallace doesn’t shy away from.

This idea of perception is critical to The Stubborn Particulars of Grace, and it’s a book that gets better when you look at it more closely. When you start to see the connections between the different components of the poems, you see a finely woven tapestry emerge. While the poems sometimes seem more personal than accessible, there’s nonetheless a kind of universality that shines through and provides some wonderful intimacy. The language on its own isn’t ornate enough to warrant quoting isolated lines, but the storylines of the poems, their meditative empathy, their calls to action, and their weaving are well worth sustained attention.

Happy reading, everybody!

No comments:

Post a Comment