It should come as no surprise that novels have multiple layers—that which the novel is ‘actually’ about (i.e. objectively, factually) and that which the novel is ‘figuratively’ about. The best novels, in my opinion, are ones where both layers are compelling: the ‘facts’ of the story are engaging in their own right, but also have that more ‘hidden’ layer that feels meaningful and relevant. All the better if the two layers interact in surprising but authentic ways. To put it another way, I’ll refer to a term one of my students invented to assess whether a book is good or not: “self-insertability”---it’s good if you can imagine yourself into the text.

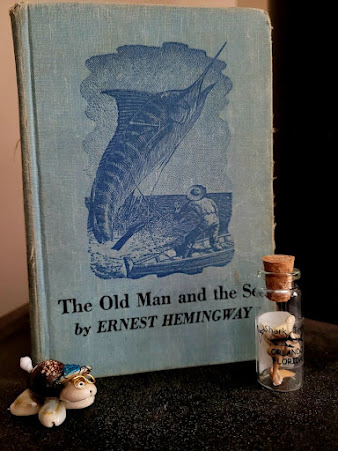

When it comes to Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, I find a pretty substantial imbalance. What the book is ‘actually’ about is boring and inaccessible. An old dude tries to catch a fish; it isn’t easy. What the book is ‘figuratively’ about is somewhat compelling: hope, perseverance, luck, connection. It’s kind of like Moby Dick but about 1/10th its length.

Coming in at about 130 pages, The Old Man and the Sea reads more like a short story than a novel. It begins with some background and character development for Santiago (the old man) and Manolin, a younger man. The two have a nurturing bond, but the young man was prohibited from joining his mentor any longer; Manolin’s parents forbid him going out on such an unlucky boat. Santiago then goes to sea alone, feeling lucky after 84 days of not catching anything. The rest of the book is him at sea—it’s a little unclear for how many days—and his attempts to ‘catch the big one.’

The book fails to resonate with me for two central reasons. The first is that the book is completely focused on fishing, which is a waiting game. Substantial portions of the text are Santiago waiting around and noticing subtleties in movement. Hemingway spends a lot of time narrating what’s happening with the skiff and the lines and the whatever else no non-fisher cares about. The second component is connected to the first: the text is full of repetition. There are certain ideas that recur over and over and over. Thematically, it’s appropriate, given Santiago’s single-mindedness, but not engaging to read. I’m not sure how many times we need references to Santiago’s cut hands, or his deciding whether or not to eat his preserves, or how he hopes the fish will start to circle, or how he likes Joe DiMaggio.

Anyway, the ‘deeper’ level of the book is what presumably won Hemingway the Nobel, so let’s chat about that. Embedded in the text are passages that clearly speak to the human experience, though the particular magic of how you know a line is ‘deep’ is not immediately obvious; I’m sure I once read an essay about how ‘key’ passages speak beyond the text, but its central thesis was essentially that the phenomenon is inexplicable. I’m getting distracted and/or avoiding talking about the text.

The highlight of the text is when Santiago hooks the marlin because it establishes their symbolic relationship. They are attached by a string (like Jane Eyre?), each pulling the other. It really drives forward the fact that they are bound up in the same experience, both fighting for their lives and striving to maintain the endurance needed to go on. Later, Santiago is looking up at the stars and the narration reads: “I do not understand these things, he thought. But it is good that we do not have to try to kill the sun or moon or the stars. It is enough to live on the sea and kill our true brothers” (74). It’s pretty on-the-nose to establish the relationship between humans and animals but is still nicely put. The idea of “killing the sun or moon or stars” comes up repeatedly and it’s an interesting idea, I suppose symbolic of the greater forces that cannot be opposed. There’s a kind of fatalism in the text where luck comes and goes and all that you can do is hope.

There’s another element of the text that I found interesting because I haven’t quite processed its purpose: the role of dialogue. Hemingway is famous for his plainspoken dialogue, so a story that is only one character for essentially 80% of its page count is an odd choice. Hemingway, though, has the old man speak to himself aloud. Practically, Hemingway could be doing this just to be more engaging and split up the narrative. I’m curious if it has a thematic significance as well. The old man says things aloud in response to the narrator. It’s an odd technique. I’m confident that someone has written an essay on that by now, but on a first read I had a hard time imagining why it matters—perhaps just because the narrator is more representative of higher powers that dictate what happens to the lowly figures below and then Santiago asserts himself in the face of fate by responding to it? There are, after all, times that Santiago challenges the narration; if it is about how hopeless the situation is, Santiago might then say something aloud like “I must retain my hope.” The contradictions would be worth exploring perhaps if I were more interested in the surface level.

In terms of foreshadowing, Hemingway is so overt as to cause almost no surprise. He heavily telegraphs that the old man’s mission will be a failure, that sharks will appear, and so on. The one thing that is not predictable is the novel’s ultimate conclusion. Everything else in the text would suggest that he is destined to die, and yet he lives and the novel ends with his young mentee tending to him and making plans for the future. The hopeful optimism they share is somewhat beautiful, and it’s an interesting flip of the expectations you have (cue the most memorable scene from Silver Linings Playbook when Bradley Cooper throws A Farewell to Arms out the window and goes on a four a.m. rant about how Catherine dies).

At this point I’ve read a reasonable amount of Hemingway and each time I’m left feeling pretty indifferent or worse. He’s alright I guess. I can certainly appreciate him grappling with larger themes and the human experience, but he always (for me) seems to miss the mark on the actual plot—don’t even get me started on the banality of cafes and bull fights in The Sun Also Rises.

Happy reading, folks! May you always catch the big fish.

No comments:

Post a Comment